Abstand

A B S T A N D ist eines der großen Schlagwörter von 2020. In diesem Jahr war er eine Maßnahme des Gesundheitswesens um die Ausbreitung einer hoch ansteckenden Krankheit zu verhindern. In der Physik kann Abstand aber auch als ein Intervall oder eine Lücke verstanden werden. In dieser Pandemie wurde diese physische Distanz zu einem Intervall für Reflexion, Selbsterkundung und sogar für größere Nähe mit unseren Verwandten und geliebten Menschen. Aber wir haben ihn nicht alle auf die gleiche Art und Weise erlebt: Der herkunftsbezogene, politische, wirtschaftliche und soziale Status hat eine Kluft zwischen den Gesellschaften geschaffen, die noch tiefer ist als die, die der Virus verursacht hat. Haben wir alle die gleiche Vorstellung von Distanz? Das Kollektiv von Künstlerinnen*, Pussart, wird sich verschiedenen und verborgenen Perspektiven der Distanz, dem Lockdown und seinen Folgen, sowie der menschlichen Einsamkeit in unserer Zeit annehmen.

Artists

Anna Sans

Becky Jaraiz

Carolina xFx

Gabriela Husz

Kristy Husz

Mina Chauveau

Paula Serrano-Espelta

Rosario Vázquez

Suzzie Qiú

Curated by Karne Kunst.

Projekt im Rahmen der Fördermaßnahme NEUSTART KULTUR. #neustartkultur

The Other Distances

In the current pandemic situation, Abstand means keeping your distance. Yet in ordinary speech Abstand can also mean an interval or a gap. For many people, this physical distance became an interval for reflection, and even one for greater closeness with their loved ones. Or simply to be more ‘connected’ (with all the pros and contras of online social networks). A pandemic is global in nature, and we have seen how a globalized world should stop seeing borders that are no longer there and advocate for more equal rights in all social strata.

Perhaps we were among the privileged ones who, initially, could take advantage of this distance, and exchange our endless business for calm and awareness; those who made good use of this ‘extra’ time to concentrate and to bring to fruition long-delayed projects. Unfortunately, after a year of the pandemic the deluge of economic and socio-political problems has impacted on most people, but to a greater extent on those who already lacked protection and were vulnerable.

We make an example of women who ever since the creation of societies are ‘shaped’ to stay ‘indoors’ while the men went ‘out there’ into the world. In this context, the phrase heard everywhere – ‘stay indoors’ – became more than a prison: an extra workload, one that of course is neither paid nor appreciated. With the schools and nurseries closed, most mothers have not only had to raise their children and look out for their general ‘wellbeing’, but become their teachers and work extra hours both at home and professionally (if they were lucky enough to keep their jobs). To these domestic labours, already invisible, were added the effort of transforming their homes into office, gym, school, conference room, studio, etc.

The virus brought with it a new series of questions, as the state began to refer to ‘essential jobs’. This concept affected men and women alike who do not work in public health or other key areas. A different kind of crisis arose as each was confronted with the non-essential character of their work. Not to speak of what this has meant for artists, whose work is often ignored in any case, and who are among the most affected by the lack of support. (By arts we include music, theatre and dance). The paradox that health workers at all levels have now been placed on the front line in terms of importance, like the warriors that they are, risking themselves in the battle, begs the question: why throughout history have the mothers who as the ‘nurses’ or ‘carers’ of families been undervalued? The question of which work is valuable and indispensable and worthy of remuneration, and which is not, opens up a large gap and a confrontation that is both psychological and political.

The panorama is still worse for less fortunate families whose physical and psychological integrity hangs from a thread, who are trapped at home, protected from the virus but at the disposal of the whims of their aggressor 24 hours a day. For the state, domestic violence does not seem to represent an equivalent danger to life because there has been little discussion about the issue.

Thus other kinds of distance appear, conjured up by economic, racial, political, and/or social disadvantages, meaning abandonment and greater marginalization. Distance ‘promised’ protection from contagion, from illness, from death. Just as ‘covering up’ your nose and mouth and washing your hands shows responsibility for yourself and/or for the other. Yet can the state wash its hands like Pilate to absolve its guilt?

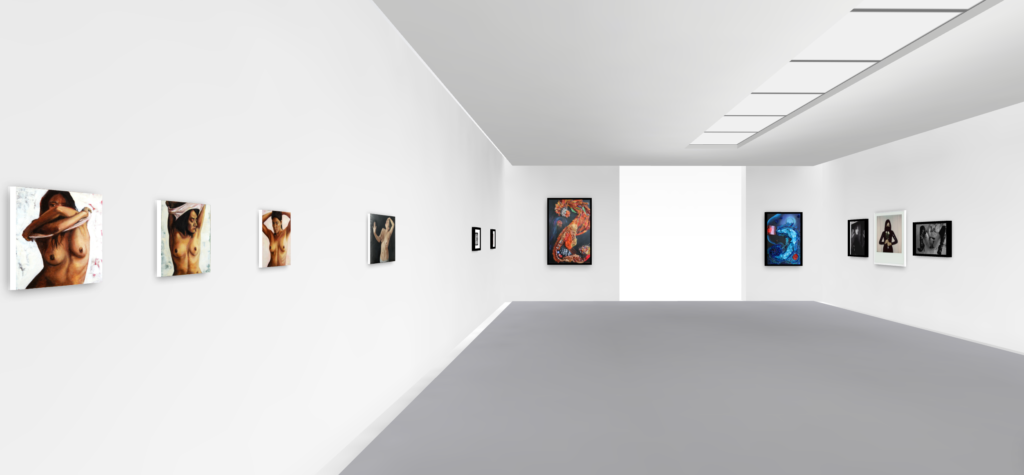

Virtual Gallery.